Conservation of Spanish Historical Heritage

We started our collaboration with the Prado Museum after signing an agreement on 24 November 2010, granting us the status of Protector Member of the Museum’s Restoration Workshop.

The Fundación Iberdrola España has been a Protector Member of the Prado Museum’s Restoration Workshop since 2010.

One of the Prado Museum’s main roles is to guarantee the protection and conservation of the Spanish Artistic Heritage assets it houses. A large part of this work is carried out by the Museum’s Restoration Area, made up of 31 specialists from various interdisciplinary departments who work together to carry out the preventive conservation, study and analysis and, when necessary, restoration of the works of art.

In June 2013, we deepened our collaboration with the Prado Museum when we signed a new agreement giving us the status of Benefactor of the Prado Museum supporting new initiatives at the art gallery such as the Lighting the Prado project, without overlooking our support for the museum’s conservation and restoration programme, which is one of the most prestigious in the world.

We also award two restoration research scholarships each year that enable the beneficiaries to further their training at the Prado Museum’s Restoration Workshop. The objective of this initiative, whose first call was in April 2011, is to complete the training of future specialists and encourage research in the field of restoration.

Restoration work

Since our sponsorship of the Prado Museum’s Restoration Programme began, interventions have been carried out on over 2,000 works. In recent years, the most important pieces restored, within the framework of our collaboration agreement, have included:

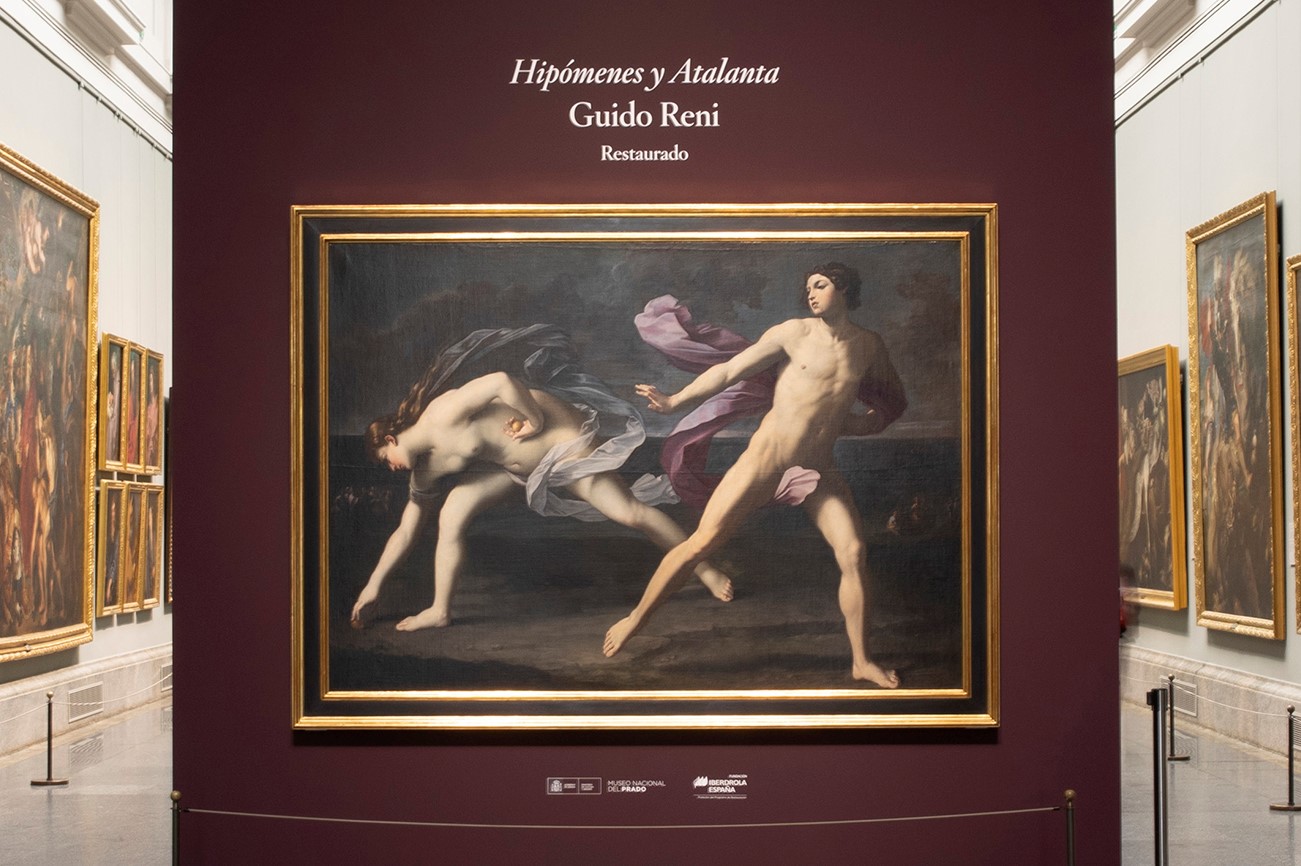

- Hippomenes and Atalanta, one of the most iconic works in the Museo Nacional del Prado collection, and one of the most famous by Guido Reni, is on display again after its restoration thanks to the patronage of the Iberdrola España Foundation

- Until next November it will hang in a special structure located in the Central Gallery, before traveling to Frankfurt, where the Städel Museum is preparing an exhibition on Reni. On its return, the work will be present in the great exhibition that the Prado Museum will dedicate to this master of the Baroque, one of the great projects of the year 2023

One of the most famous works by Guido Reni, which entered the Prado Museum as part of its founding collection, Hippomenes and Atalanta, can be seen today in a special installation located in the Central Gallery. Thanks to its recent restoration and the provision of a new frame, it will be possible to appreciate the composition as the Italian master conceived it.

The restoration work, carried out with the support offered each year by Fundación Iberdrola España, Protector of the Museo Nacional del Prado’s Restoration Program, has shown that it is truly a work of great luminosity and expressive strength, far from the “caravaggiesque” appearance that it had acquired with the aging of the materials over the years. During this intervention, which lasted nine months, it has been noticed the existence of two bands added in the left and lower areas that were not original to the master, also restoring its original vision.

The work can be admired in this special installation until the first week of November this year, when it will leave the Museum to participate in the exhibition on Guido Reni that, in collaboration with the Prado, the Städel Museum in Frankfurt is preparing. In 2023, it will return to be present at the Prado’s major exhibition on Guido Reni (March-July 2023) where it will share space with the analog version kept at the Museo di Capodimonte.

The restoration

The main objectives of the restoration, carried out by Almudena Sánchez, were, on the one hand, the removal of the oxidized varnishes that transmitted a yellowish tone to the painting, especially warm on the flesh tones of Atalanta and Hippomenes and, on the other hand, the regeneration of the altered and opaque areas. Former interventions were the cause of the numerous and extensive repainting that over time were degraded to become very disturbing stains that have survived until today and that were another very negative factor for the aesthetic appearance of the work. In addition, the painting was reframed and the size of the work was enlarged with two bands of the canvas, one of 7 cm on its left edge and another of 13 cm added to its lower edge, thus altering the original size of the composition.

Fortunately, the transparency of the varnish has been recovered, through which the color of the painting that had remained hidden can be appreciated. A good example of this is the recovery of the hair of Hippomenes, in which the opacity of the varnish had annulled the brown tone and the volume of the curls located at the back of the head. But the most decisive area for the recovery of the space and the different planes of the composition was undoubtedly the strip corresponding to the sea, which responded positively to the treatment in such a way that the whitish and opaque layer gradually became transparent, bringing to the surface the dark blue of the sea.

During the last phase of the restoration, the chromatic reintegration of all the damages and lack of color that had been exposed after the elimination of the old repainting that hid them was carried out. Particularly noteworthy is the reintegration of the loss that followed the line of the seam from one end of the painting to the other, passing through the bodies of the two characters, fundamentally the recovery of the beautiful profile of Atalanta, in which we can now appreciate the delicacy of her features and the subtle rosiness of her cheeks.

Once the restoration is completed, we can appreciate an image of the work much closer to that conceived by Guido Reni, for the recovery of light, color, and space in which the scene takes place and, above all, because the two striking figures of Hippomenes and Atalanta, recover the strength of the anatomies and the sharpness of the flesh tones elaborated with subtle shadows with which Guido Reni is modeling the bodies in movement, those beautiful bodies that have always captivated the viewer and now do so with greater intensity.

Download information and images

https://www.museodelprado.es/museo/acceso-profesionales

Guido Reni 1618 – 1619. Oil on canvas, 206 x 279 cm. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Guido Reni 1618 – 1619. Oil on canvas, 206 x 279 cm. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

This is one of the most famous and controversial works of this artist and, in general terms, of the Bolognese Baroque. This painting was part of the collection of the Marquis Giovan Francesco Serra, a collection that was acquired in 1664 by Gaspar Bracamonte y Guzmán, Count of Peñaranda and Viceroy of Naples from 1658 to 1664, destined for Philip IV. It entered the Museo Nacional del Prado with the foundational funds and was exhibited in the Sala Reservada from 1827 to 1838 along with 73 other nude works.

The story tells how Atalanta, daughter of a king of Arcadia, had offered herself in marriage to whoever was able to beat her in the race, a sport for which she had achieved an outstanding ability. The punishment established for all those who were defeated was death. Despite the risk, Hippomenes accepted the challenge with the help of Venus, who provided him with three golden apples that the young man threw as he went along, thus managing to delay Atalanta who stopped to pick them up. However, once married, Hippomenes forgot to thank the help of the goddess who had brought about his victory, which ended up metamorphosing the two into lions. Reni resolves the composition by placing both figures in the foreground, thus creating a diagonal structure that reflects a specific moment in the narrative, when Hippomenes throws an apple that Atalanta picks up, a circumstance that in the end will be the cause of his defeat.

Many of the essential characteristics of Reni’s art are present in this fundamental piece of his catalog. His classicism is manifested, not as archaeological clothing but rather as a motif of formal reflection, in the vigorous anatomies, or in the frieze distribution of the characters that interpret the drama. And also, on different terrain, in its ideal of beauty, which is manifested in the formal perfection of the naked bodies, in their almost symmetrical balance, and in their dramatic qualities, which are expressed through restrained attitudes, even though they are in the middle of a race that will decide the fate of both young men. In all of this, color plays a fundamental role.

Fundación Iberdrola España, Protector member of the Prado Museum

Fundación Iberdrola España develops one of its main lines of activity around the care and maintenance of the cultural and artistic riches of our country.

Fundación Iberdrola España acquired the status of “Protector” of the Museo Nacional del Prado in 2010, through its support for the conservation and restoration programs of the art gallery, as well as the development of 4 annual scholarships for young restorers. Thanks to this collaboration, it has been possible to carry out interventions that have given back to great works of the Prado collection the luminosity and depth with which they were conceived, such as Dürer’s Adam and Eve, The Wine of the Feast of St. Martin and The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel “the Elder”, La Gioconda from Leonardo’s workshop, The Adoration of the Magi and The Temptations of St. Anthony by Bosch, The Annunciation by Fra Angelico, The Countess of Chinchón by Goya and most of the pieces from the Treasure of the Dauphin.

It also wished to join the Extraordinary Program for the Commemoration of the Bicentenary of the Prado Museum and, specifically, the deployment of this traveling exhibition in Spain.

Since 2011, Fundación Iberdrola España has allocated a total of 13 million euros to the area of Art and Culture, which focuses its resources mainly on the Restorations Program, which supports the restoration workshops of leading museums for the conservation of their pictorial and artistic heritage; and the Illuminations Program, which includes the design, execution, and financing of artistic lighting projects in unique buildings and monuments.

The portrait of The Countess of Chinchón is an oil painting on canvas in an exceptional state of conservation. Its recent restoration began in March 2020, but little is known of previous interventions. In 1988 and 1996 small areas of the pictorial layer were consolidated in the Prado’s workshops for the exhibition of the work in the Museum. After its acquisition in 2000, a technical study revealed that it was painted on top of a canvas already used by Goya, in which a standing portrait of Godoy and a less visible, underlying portrait of a young knight wearing the cross of the Order of Saint John of Malta on his chest can be fully identified in the X-radiograph. Both were covered by a pinkish-beige cloak, used in preparation for the final portrait of the Countess of Chinchón.

The current intervention has reinforced the corners of the original canvas, which is uncovered, and several patches of cloth applied in the past over small tears have been replaced with linen thread. It was important to fix the pictorial layer and the preparation, due to the presence of craquelure that posed a risk of detachment. The last phase of the restoration consisted of removing the oxidised varnish and the dirt accumulated on the surface of the painting.

The cleaning process has been key to appreciating Goya’s masterly brushstrokes, which were covered by a dark, yellowish veil that prevented the depth and air of the space surrounding the figure from being captured. Now, with the transparency of the new varnish, it is possible to distinguish the green tones of the spikes on the headdress, the precise quality of the gauze of the dress and its embroidered ornaments, and the subtle shades of grey and white. The pearly flesh tones and the blush on her cheeks and the fine, curly hair that seems to move before her eyes with their rapt, clear gaze perfectly describe the character of the young countess.

The Countess of Chinchón. Goya

The portrait of the Countess of Chinchón is documented in the correspondence between María Luisa and Godoy between 22 April and early May 1800, when the Queen was finalising preparations for Goya to paint The Family of Charles IV in Aranjuez. It is known from the letters that Maria Teresa was pregnant again, two previous pregnancies having been frustrated. A baby girl, Carlota Joaquina, was born on 2 October of that year, and was sponsored by the king and queen.

The young woman’s headdress, with its ears of wheat, was in keeping with the fashion for women’s adornments of those years, which included flowers and fruit, but here it has the added significance of being an emblem of fertility, being the symbol of the goddess Ceres, whose festivals were celebrated in ancient Rome precisely in the month of April in which the painting was painted.

Depicted in accordance with the high rank she now held, full-length, seated in a gilded armchair that resembles the throne of her ancestors, as the granddaughter of Philip V, and awaiting the heir who was to be both son of the Prince of Peace and descendant of the house of Bourbon, Goya was able to capture all the naivety and candour depicted by Godoy in his letters. On the left hand he wears a ring, whose precise, well-defined central brushstroke highlights the brilliance of the diamond, and on the right another, on the middle finger, adorned with the miniature of a very sketchy male portrait wearing the blue sash of the order of Charles III.

The half-light that surrounds her is far removed from the light of the portraits of other aristocratic ladies and recalls, with its Velázquez-like use of dense shadows and the illuminated figure, some contemporary prints from the Caprichos.

The figure is subjected to a rigorous geometry and the folds of her gauze dress create a set of richly criss-crossed planes that suggest volume and increase its luminosity. The floating spikes and blue ribbons seem to move, revealing the slightest movement of her head, and the white ribbon of stiff organdy, which holds the bonnet under her chin, projects a rigid ribbon under her face which, with its three white brushstrokes, full of matter, emphasises the rosy colouring of the young woman, the fineness of her face, as well as her sweetness and the nervous and repressed expressiveness of her personality. Although the fluidity of the technique, the lightness of the brushstrokes and the little material used to paint it stand out, revealing the warm, pinkish preparation an unknown gentleman and of Godoy himself.in many areas, there is nevertheless an elaboration of the figure in all its details, which Goya completed with rigorous technical precision and dense material, perhaps used to conceal the fact that he had used a used canvas for such an important patron in which there were already two fairly finished portraits of

The Countess of Chinchón

María Teresa de Borbón y Vallabriga, born on 26 November 1780 in Velada, was the daughter of Prince Luis de Borbón, brother of Charles III, and María Teresa de Vallabriga, a lady of the Aragonese nobility. Removed from the court from birth along with her siblings, and unable to use the surname of Bourbon by the Pragmatic Sanction of Charles III, on the death of her father in 1785 she was sent with her sister to the convent of San Clemente in Toledo, from where she left to marry Godoy on 2 October 1797.

The marriage was decided by decree of Charles IV. The young María Teresa, then sixteen years old, after being consulted, agreed to the marriage, which restored family harmony in the House of Bourbon and rehabilitated the three brothers and their mother, restoring their royal surname and titles. On the other hand, the king and queen were honouring Godoy, their most trusted man, by linking him to royalty.

The work The Fountain of Grace regained its splendour thanks to the works carried out by the Prado Museum, with our support.

After fifteen months of restoration work, the Prado Museum has regained the splendour of the work The Fountain of Grace, thanks to our support. It is one of the museum’s most important and enigmatic Flemish paintings due to the different theories about its authorship, origin and meaning.

After a long process of restoration, the Prado Museum was able to exhibit three little known masterpieces by the artist Antonio María Esquivel, one of the most outstanding Spanish Romantic painters.

The Prado Museum, with our support, restored and exhibited 3 little known masterpieces by Antonio María Esquivel.

- Of the three works, The fall of Lucifer, The Saviour and The Virgin Mary, the Baby Jesus and the Holy Spirit with Angels in the Background, only the former had been exhibited previously, and only for a short time, in the Casón del Buen Retiro.

- The three works were restored in the Prado Museum’s Restoration Workshop, paying special attention to cleaning and repairing the wear caused by the passage of time in order to restore the perfect balance in the composition as well as the colour tone and light that characterise Esquivel’s work.

The paintings by the Sevillian artist were restored within the framework of our collaboration with the institution and were exhibited in the museum until 20 January 2019 in a room dedicated to the great works from the 19th century.

- The painter’s religious work does not receive the acclaim it deserves as Esquivel is better known for his portraits, so the exhibition aimed to try to fill this gap.

- The exhibition reflected the main elements of Esquivel’s style, which was influenced by Andalusian Baroque painting and, in particular, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

It is a moralistic work that depicts the triumph of Death over worldly things.

This painting, one of the masterpieces in the Prado Museum, returned to its rooms after restoration work lasting a year and a half. The work, from the Royal Collection, was the only painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder that was held in Spain until The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day also entered the Prado’s collection in 2011.

It is a moralistic work that depicts the triumph of Death over worldly things, a common theme in medieval literature, and was influenced by Bosch.

The restoration process of The Triumph of Death, a 117 x 162 centimetre oil painting on wooden panels, carried out by María Antonia López de Asiain (on the pictorial surface) and by José de la Fuente (the support), reinstated its structural stability, its original colours, its composition and its highly personal pictorial technique that, with precise brush strokes, achieves transparency in the backgrounds and prodigious sharpness in the foreground.

Restoration

The four horizontal oak panels on which the work is painted were taken apart, at an unknown time, to plane them and the support was reinforced with a seam system that prevented any natural movement in the wood.

Given the state of conservation of the support, in this action the seaming was eliminated to release the natural movement of the wood and level the cracks and panels, separating the upper panel to balance it correctly in the plane.

Once the restoration of the cracks and joints was completed, a secondary support was built – a beech wood frame – with the exact shape of the curvature that the work adopted once freed from the seaming, to give it stability while respecting its hygroscopic movements.

The frame was joined to the painting using a system of flat stainless steel springs, reversibly glued to the support by golden brass buttons. These springs are inserted in nylon screws that allow tensioning, dilation and contraction movements across 3600 within the plane.

Pictorical layer

The very conception of the painting conscientiously draws attention to the final profiling of the details which had become hidden under a large number of overpaintings from different previous restorations. These were later masked by coloured varnishes to give it a unity that completely transformed its image into an almost monochrome ochre. The work, therefore, required a complete cleaning that was hampered by the delicacy of the original layer of paint compared to the thickness and hardness of the repainting.

- Removing the general repainting has eliminated the warm-toned veil added in earlier restorations, thus revealing previously concealed details in the original painting.

- The general tone of the painting has changed: it has recovered its intense blue and red tones, the complexity of its composition and the depth of the landscape has been restored.

Thanks to the infra-red reflectography used by the restorers and the copies of the painting made by the author’s children, it was possible to correctly reintegrate the small lost elements erroneously invented in previous treatments.

The Dauphin’s Treasure includes “rich glasses” in rock crystal and hard stone, many with trimmings made from gold and silver, enamels and precious stones.

In 2018, as part of the room remodelling started for the Prado Museum’s 2009-2012 Action Plan, the new display for the Dauphin’s Treasure and the refurbishment of rooms 76 to 84 were inaugurated to present the 17th century Flemish and Dutch painting collections. Both sets are now exhibited on the second floor in the north wing of the Villanueva building, in renovated areas to highlight the richness and variety of these two collections.

The collection is named after the Great Dauphin Louis of France, son of Louis XIV and Maria Theresa of Austria, who gathered together a fabulous collection of “precious glasses” in rock crystal and hard stone (agate, jasper, lapis lazuli, jade), many of them garnished with gold and silver, enamels and precious stones.

The Dauphin was never crowned and his son Felipe V, the first Spanish Bourbon, inherited 169 works known as the Dauphin’s Treasure. They were very popular at the time: costing five times more than a Titian.

- It is the only collection of its kind in Spain, comparable to other great European dynastic treasures, both for its quality and its intrinsic value and beauty. It is also an important example of a European collection of 16th and 17th century decorative arts, which projected an image of royal power and prestige.

- Currently, this treasure is displayed in the circular room that surrounds the dome in the upper Goya Rotunda. This 188-square metre room contains a spectacular curved glass cabinet that is 1.73 metres high and 40 metres long and houses 170 exquisite and refined pieces.

The In Lapide Depictum exhibition focused on painting on stone from the Renaissance period.

The Prado Museum, with our collaboration, showcased an exhibition dedicated to Italian painting on stone (In Lapide Depictum) to show the public the results of the studies carried out during the restoration of these works. The exhibition was curated by Ana González Mozo, Senior Museums Technician with the Prado Museum’s Restoration Area.

- The carefully selected group of works from the Museum’s collection, together, along with two others from Naples, revealed the new approach to artistic techniques that emerged in the early decades of the 16th century.

- The exhibition also reflected the aesthetic and philosophical concepts of the time: the reproduction of new pictorial effects which entail controlling how the light falls on the painting’s surface; the perception of the natural world as codified in classical texts; the paragone (comparison) with sculpture; and the desire to produce eternal creations.

Although there have been some previous exhibitions of a general nature, the Prado Museum wanted to delve into this phenomenon, studying the theories that stimulated its development and exploring the origin of the technique, its relationship with the classical world and the painting techniques honed by Sebastiano del Piombo, Titian and Daniele da Volterra to achieve different chromatic results. Thanks to the use of these non-traditional supports, the works have reached us in a good state of repair.

For the exhibition, and within our collaboration programme with the museum, restoration was carried out on two works by Titian and one from the Bassano workshop. The pieces underwent lengthy and delicate restoration involving a number of specialists in different areas of restoration (paint, frames and supports), so that visitors can fully appreciate the uniqueness of these works, executed in oil on supports that are both special and rarely encountered in the history of art.

- The two paintings by Titian, which were painted on a stone support for Emperor Carlos V, were in very poor condition due to the large amount of surface dirt and accumulated oxidised varnishes. The restoration of Ecce Homo by Elisa Mora recovered its hidden nuances, revealing how Titian (taking advantage of the dark slate base) used glazes to depict the flesh and volume of Christ’s anatomy and the textures of the fabric mantle. In Mater Dolorosa, transparencies, shades and nuances of colour were discovered in this unprepared painting whose luminosity is due to its white marble support sealed with hot oil.

- The Holy Burial from the Bassano workshop was restored by Alicia Peral, who recovered the volume of each figure and its exact position in the composition, as well as the depth of the landscape. The restoration also revealed touches of gold with which the author achieves the effect of vibrating light, in contrast to the dark, deep surface of the slate support.

The nature of the support and the close relationship established with the classical tradition of polychromed stone has encouraged a collaboration with other disciplines, including natural history, geography and archaeology. This collaboration yielded a greater understanding of the techniques used and of the works themselves, which was reflected in different aspects of the exhibition:

- On the one hand, through the presence of pieces belonging to these fields: works from the classical Roman world and rough stone materials, to help contextualise the selected paintings.

- On the other, in a series of very specific studies, carried out with specific means from the aforementioned disciplines.

Fundación Iberdrola España helped with the restoration of this emblematic work from the reign of Philip II.

This canvas commemorates two events of enormous importance for Felipe II which took place in 1571: the victory at Lepanto (7 October) and the birth of his heir (4 December).

Philip II chose this work to represent his reign and paired it with the portrait of his father, Carlos V at the Battle of Mühlberg, also by Titian. From then on they were always hung together and, in order to display the painting in the Salón Nuevo in the Alcázar, in 1625, he requested that the painting be enlarged to give it the same dimensions as the equestrian portrait of the emperor.

Restoration

Carried out by Elisa Mora, with our sponsorship as benefactors of the Restoration Program, the restoration recovered the qualities of Titian’s original but it also made Carducho’s enlargements more visible, particularly in the architectural elements. After the presentation, the canvas was put on display with the enlargements made by Carducho hidden from view.

The first known restoration of this painting took place in 1857 when it may have been relined. Almost a century later, in 1953, the AMNP’s records show that the restorers Martín Benito and Lópe Valdivieso worked on Titian Victory at Lepanto. Lay colour, restore, clean and check.

The most recent restoration, which began in January 2016 and concluded in May 2017, was extremely complicated given the painting’s size and state of repair.

- Following analyses undertaken in the Museum’s technical documentation section and chemical laboratory, work began with the removal of surface dirt, oxidised varnishes and old areas of repainting from previous restorations.

- This cleaning, which uncovered some old losses, cracks and infilling with gesso, was undertaken in successive stages until Titian’s original could be revealed with all its characteristic pictorial technique. After cleaning, two large losses that had been repaired with inserts in the past became visible between the table and the King’s left arm.

- The additions made by Carducho were found to be damaged and repainted, particularly in the left part of the sky. After eliminating these hard areas of repainting, significant losses and worn areas became visible. The blue pigments used by Carducho, which were different to those used by Titian and of inferior quality, had aged differently and altered, making his modifications visible, particularly in the Turk’s stockings.

- Once the cleaning was completed, the pigment was fixed in the areas found to be fragile and or with irregularities along the seams of the added areas.

- In order to restore the largest areas of paint loss, silicone moulds were made that reproduced the texture of the canvas and thus the characteristic oscillation of Titian’s surfaces. Areas of paint loss and wear were first reintegrated with watercolour then, after the missing areas were filled in and the painting varnished with natural resin, a final adjustment was made to the colours.

Fundación Iberdrola España sponsored the restoration of this head, part of a monumental bronze statue.

The Prado Museum exhibits a monumental bronze head identified as that of Demetrio Poliorcetes (h 336 – 283 BC). The piece, which was prominently displayed for a number of months in the lower Goya rotunda in the Villanueva Building, recovered for public exhibition after the restoration we sponsored. It is one of the few Hellenistic sculptures of this size and quality still existing. It is not known where the head, which measures 45 cm, was found, but it probably belonged to a monumental statue some 3.50 m tall. The preserved sculpture that is closest in appearance to this one is the Potentate of the Baths (Museo Nazionale Romano), although it was created some 150 years later and is over a metre shorter.

The high quality of this bronze can be seen particularly in the masterly crafting of the hair, with tight curls that loop around the head in a lively fashion, and the mastery of the lost-wax casting.

- In Greek sculpture, this technique was used to cast small pieces, such as heads, torsos, arms and legs, which were then assembled to create a large sculpture.

The piece was previously in the collection of Queen Cristina of Sweden, its first know owner. On its arrival in Spain in 1725, it was kept in the Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso with the collection of Philip V and Isabel de Farnesio and it was added to the Prado Museum’s collection in around 1830.

Through recent investigations, the figure depicted was identified as the Hellenistic general and king Demetrius I, called Poliorcetes because of his outstanding, and successful, sieges of enemy cities (336-283 B.C.). Together with his father, the Diadochus Antigonus I, Demetrius was the first successor to Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.).

The condition of the sculptural portrait of Demetrius Poliorcetes reflected the perilous journey made by the piece over the centuries and the many interventions to which it had been subject. In order to preserve it, these interventions hid the original bronze surface under layers of glue, tar and paint.

The technical studies made prior to the restoration process provided important data on the casting process and the history of this portrait. They also brought to light the stability problems of both the metal itself and the structure, information that was needed to define the goals and the most appropriate treatment for the intervention.

The priorities in this restoration were to give the sculpture back its original surface and colour, making it more legible, and to stabilise and protect the materials that comprise it, especially the bronze. A further priority was to strengthen the internal structure to prevent the structural tensions that had caused cracks, by designing a stable, resistant support that would avoid covering areas of the original surface.

- The restoration process consisted of removing from the bronze surface the resins, glues, protective coatings and tars from previous interventions, as well as relocating some fragments to their original position; then designing new temporary and reversible attachment systems.

- After the restoration of this piece, and to better preserve it, a specific support was designed, lined with a cushioning material that spreads the weight of the sculpture over the support, preventing the supported areas from becoming pressure points. In addition, a system of hidden pads was proposed, which are taken out during transfer and permit the sculpture to be moved safely without the need to directly touch the bronze.

The identification of the figure portrayed was a complicated task because it has no unmistakeable characteristics and the features do not clearly match those in any portrait. Due to its ambiguous typology, the work offers two different messages, depending on whether it is viewed from the front or the side.

- Viewed from the front, the idealised typology Greek art used to depict gods and heroes can be seen, like those created by the classical Greek sculptor Scopas around 340 B.C.

- However, when viewed in profile, the traits of a portrait can be recognised: a bulging, muscular forehead, deep-set eyes, an oblong face and a slightly open mouth.

Alexander the Great, who was seen as a god and a hero, was the first to be depicted using this type of portrait, which was then imitated for the Diadochi, the generals who succeeded him. A marble portrait, found with other portraits of Hellenistic sovereigns in the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, which is interpreted as being a portrait of Demetrius Poliorcetes, shares a similar hairstyle and the same facial features with the monumental head, as does another marble portrait in Copenhagen.

Demetrio Poliorcetes

After Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., the diadem, a band knotted around the head that signified his absolute power over Asia, became the most important insignia of the Hellenistic kings. However, this diadem does not appear in the portrait of Demetrius Poliorcetes and other similar portraits. Today, its absence makes it difficult to identify the portraits of the Diadochi. One reason was that after the death of Alexander the Great they did not dare to depict themselves as being like him. In 307 B.C., Antigonus I and his son Demetrius I, who was almost 30 years old, were proclaimed kings by the Athenians, but, according to the Greek writer Plutarch, they both avoided using the name of king as this was a unique regal attribute reserved exclusively for the descendants of Philip and Alexander. A year later, in 306, when Demetrius Poliorcetes defeated the fleet of the Diadochus Ptolemy (367-283 B.C.) in Cyprus, the assembled Macedonian army declared Antigonus I and his son Demetrius I to be kings of Asia and sent them the diadem as the successors of Alexander. According to this detail, the absence of the diadem suggests that the bronze in the Prado was created before this event, in 307 B.C., when Demetrius Poliorcetes and his father Antigonus I were the kings of Athens.

- The collaborations that we establish with the museum also include the exposure of the youngsters on the With a Smile programme to restoration work, as part of their artistic and cultural training.